No Premium on Haste: Anthony Hecht's "Flight Among the Tombs"

Soon it will be May, the season of the Kentucky Derby. Before the race begins, with the properly fine society, the men and women placing bets on the ponies, there is another among them, omnipotent and unknown. Watching all the living, Death speaks:

Among these holiday throngs, a passer-by,

Mute, unremarked, insouciant, saunter I,

One who has placed —

Despite the tumult, the pounding hooves, the sweat,

And the urgent importance of everybody's bet—

No premium on haste.

The attendants get their rush on competition, and this eagerness for a choice horse to win big is entwined with the fact that at some point these people, outside their imaginations, will stop breathing.

Death, on the other hand, has no competition, and no concern for chance — not even for educated guesses. The living make educated guesses, like the men who "advance / questions of form" upon the horses' breeding and racing stats. In Anthony Hecht's poem, "Death Sauntering About," we see his ironic characterizations of death begin. The first of 22 monologues in Flight Among the Tombs, where Death, the grim reaper you think of that dons black robes and carries a scythe — Death — , strikes back against societal hubris and warns of his categorical advantages over the living.

Death is at the horse tracks. Death is also an Oxford Don, and there's "Death the Archbishop," and "Death the Film Director," and "Death the Mexican Revolutionary," and there's death portrayed as a clownish puppet ("Death the Punchinello") who always gets the "terminal ha-ha."

The living, to Death, are his punchlines. He is always there, slightly benign until he isn't. "Death the Carnival Barker" cries out to the crowds in his tent, "Fear not, my friends! There's room for everyone! / Step forward, please! Make room for those in back!"

Hecht was the twentieth century’s most baroque modernist. His first book, A Summoning of Stones, was published in 1954. Forty-four years later, when Flight Among the Tombs was published, Hecht had built his reputation as a modern master of poetic forms. Perhaps at times too European for most Americans, and too American for Europeans.

This is to say, his decoration could make him slower to make up his meaning, like an oboe that wanders from its initial phrase in one of Handel’s concertos to form unexpected themes. Speaking of rhythm, poems like "Death Sauntering About" can be tough on the reader's ear. In the sixteen lines of a mostly pentametric and rhyming poem, not a single line has a metrical twin. Where he took his liberties was completely up to him.

Another example: "Death the Knight." He fluently moves from French idioms to campy transgressive punch lines in English. Let's see the poem in full:

I am my lady's champion, a knight sans peur,

Though bitterly reproached by everyone.

She is the world's night nurse and paix due coeur,

Faithful and chaste as a dark-habited nun.

When in my armor I am coldly dressed,

My noble lady's favor you may see

Boldly displayed upon my helmet's crest.

Defer to her: La Belle Dame Sans Merci.

With the exception of a few widely anthologized poems, Anthony Hecht also earned an unfortunate reputation during the fifties and sixties for being a tightly sealed baggie. But is this poem stuffy? If you don't know French (I, for one, do not), then look up the phrase sans peur et sans reproche. Those first two lines are like an erudite sot, sobering up only enough to deliver a practiced and droll wise crack. If you can stand a good morbid laugh over your impending death, this is seriously funny stuff. Thrown in with the nod to John Keats's "La Belle Dame Sans Merci," which tells the story of a chevalier’s dirty romp with an elf, the schoolboy remark about the nun's dark habit would have earned Hecht a slap on the wrist with a ruler.

His style is slow-but-sure. The poet JD McClatchy, who interviewed Hecht for the Paris Review, remarked of the poet, "At times he's been unpopular." I do not think Hecht's critics are always wrong. And yet those poets he was compared against — I'm thinking of the beatniks, the confessionals, and a few other formal poets of that era when poetry mattered to the public (yes Elizabeth Bishop, yes Richard Wilbur, yes Donald Justice) — also succumbed to boorish habits of their own extremes that have at times deterred me too

The trouble with clever boys, in general, is no one likes to be laughed at. I did grow tired of being the brunt of Hecht’s jokes. I got it. I’m going to die.

I even invented a small list of titles that Hecht could have used in his book:

Death the Pomeranian

Death the Prima Ballerina

Death the Real Estate Agent's Wife's Instagram Account

Death the Pour-Over Coffee

Death the Dr. Who Rerun

The conceit would basically be the same. (You're going to die.) He bores into the reader with an anti-elegy. The poems in this first section, entitled "The Presumptions of Death" will come to a frightening crisis that Hecht pays no mind to rush to. Instead, like Death at the Kentucky Derby, the poet takes his slow, methodical pace. Hecht, who died 2004, survived the post-war generation of electrified verse comprised of poets that found new ways of talking about death (yes Sylvia Plath, yes Anne Sexton, yes John Berryman). Hecht endured by working on his craft without wholly sacrificing his personhood to the discussion. In “Death the Inquisitor,” Death is the world’s leading biologist:

Who has searched more deeply,

Or reached a more perfect understanding?

…

Who shall number the generations of the microbe,

Or the engenderings of the common bacillus?

Who has attended the pathologies of the whelk,

Or measured the breathing of the lung fish?

I abide the corruption of the tungsten,

The decay of massed granite.

I shall press to the core of every secret.

There is no match for my patience.

Death comes to the worms and spiders and microbial organisms. Death also comes to Shakespeare, who is now underground someplace and resides “with Grub Street hacks he would despise.” Death levels the proud. For those without an evolutionary capacity for pride, it simply continues to happen.

There’s nothing funny about death. (Read "More Light! More Light!" if you think Hecht took the topic seriously.) When the poet gazed into society's ways, however, he saw a cultural tendency to deny death, to wash it from our imaginations. As though to think (and how can we help it?) if we are strong-willed, or careful enough, or smart enough, in love enough, that death can't befall us. Oddly, the alternative, an abundance of death, can also have a negative effect. In "More Light!" Hecht wrote of an execution and burial scene outside a German concentration camp, saying, "Much casual death had drained away their souls." There was never anything casual about Hecht's handling of the literal subject of death.

The book's first half builds up to a poem called "Death the Whore," a poem where a man sees a smoky sky in Germany and is reminded, absent-mindedly at first, of a discomforting vision of his past. And then the horror sets in as he remembers in detail how his hunger for desire led to the death of a woman that he once knew well. The poem is of a genre called the dramatic monologue. The grim reaper steps away for this poem. It is a soft, tender, even seductive confession, one of Hecht's very best. Told by a prostitute who has died, it is ghost story.

What is death here? It is a memory.

The crisis that all the poems have led up to, here it is. A man so hungered to feed his lust, thinking himself immortal, shed everything decent thing about himself. So what is the source of his fear? An inkling of his own death? His desires that aligned so closely with hers, but she died instead of him? Whatever it is, she warns him, "It may go on for months, perhaps for years." This dramatic monologue is the first instance in the book where a character needs to address his dread, his unspeakable fears.

One pleasure of reading a poet's lyric sequence that hones such distinct erudition, prosodic skill, and sly ventriloquy is the reader's search for some sort of cohesion in the greater sequence. Does the voice of the woman slip beneath the high-brow preening of the previous poems, and make her a distinct Other for her addictions, depression and wish for oblivion? Or, when a memory lost is regained again with so much precision that it inspires fear and woe and sympathy, does the account exit the formalistic rhythms of pretense like a skillfully played oboe from an adagio?

The second section, entitled "Proust on Skates", concludes the book with many of the themes raised in first section. The book's title, Flight Among the Tombs, comes from the English poet Christopher Smart's poem "Jubilate Agno," a faux-naif poem that digs up the dead to tell the reader which ones are truly blessed. To get a gist of the tone, Smart names all the reasons that his cat Jeoffery is blessed. Among them, "He purrs in thankfulness, when God tells him he's a good Cat."

The second half feels much like "Jubilate Agno," where Hecht challenges the revered and the heroes of history. For those who are blessed, he pays tribute. But among the dead, you can read some pretty ugly ideas you'd like to see buried back, such a translation of section 25 of Horace's first ode. The translation conveys a deplorable picture of the rhetorician who very well could have been source material for the man in "Death the Whore." There is another translation of a misogynist fragment attributed to the Greek boar hunter, Meleager, called, "The Message." Meleager tells his servant to get the attention of a woman he cares nothing about so the hero can seduce her.

We do also read Hecht redeeming the elegy to preserve the memory of people that have died, and these poems are some of the finest in the book. The poems keep a mind to the regularity of death, such as the poem entitled, "For James Merrill: An Adieu":

The daily press keeps up-to-date obits

Cooling in morgues and is piously prepared

For the claim that any day may be one's last.

Dictators, famous short-stops, felons, wits

Intimately recline in darkly shared

Beds of fine print, their leaden, predestined past.

But you, dear friend, managed to slip away.

The poet who had kicked around the elegy in the dirt creates marvelous homages to artists of the past who endured the worst of traumas but managed to pursue their god-given talents and give life to their art and to their followers. For Matisse, Hecht enlivens the scene of two women painted in a blue room:

Once out of nature, they have settled here

In this blue room of thought, beyond the reach

Of the small brief sad ambitions of the flesh.

The poem that gives title to the section, "Proust on Skates," recalls the slightest marginalia of the novelist, an instance when, nearing his own death, he went out to the country with two friends to go ice skating.

On a subtle, long-drawn style and pliant script

Incised with twin steel blades and qualified

Perfectly to express,

With arms flung wide or gloved hands firmly gripped

Behind his back, attentively clear-eyed,

A glancing happiness.

It will not last, that happiness; nothing lasts;

But will reduce in time to the clear brew

Of simmering memory

Nourished by shadowy gardens, music, guests,

Childhood affections, and, of Delft, a view

Steeped in a sip of tea.

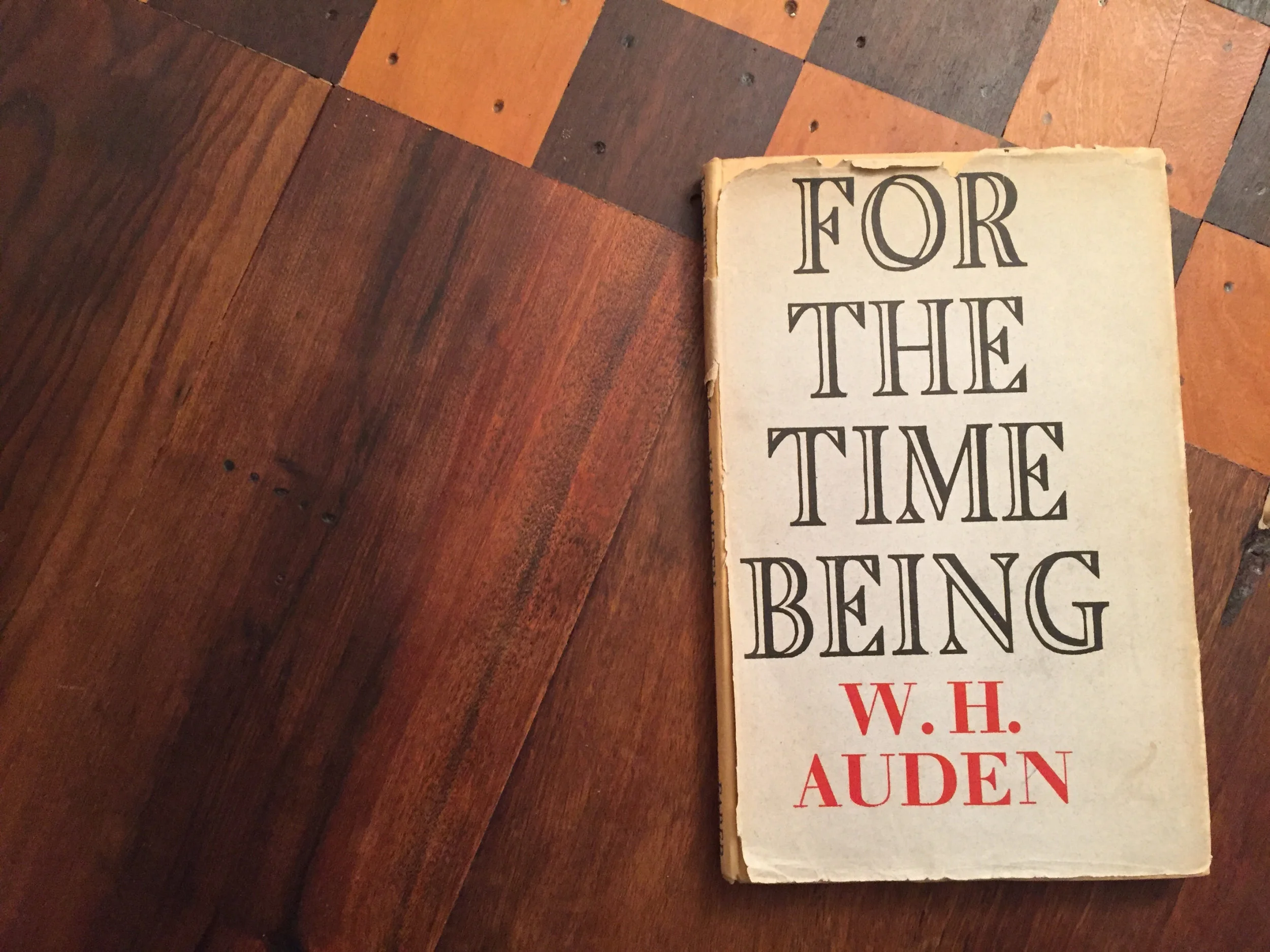

There is a debate in modern poetry about whether verse makes anything happen. WH Auden said it couldn't. Instead, the consciousness shared between two minds only suggested that something deeply ingrained in us has changed. Sharing a consciousness with Hecht by way of Death — or Death via Hecht — informs the mind of the sweetnesses and hardships of a life lived, one ideally without boasting, but one with misfortune all the same, that ends as it was sure to.

Hecht concludes his book with "A Death in Winter," a poem written in the memory of Joseph Brodsky. The poet finally turns his gaze away from the past, saying to the person holding the book,

Reader, dwell with his poems. Underneath

Their gaiety and music, note the chilled strain

Of irony, of felt and mastered pain,

The sound of someone laughing through clenched teeth.

Twenty years since Flight Among the Tombs was published. The slow, serious laugh of another deceased artist persists.